How We Monitor and Treat Type 1 Diabetes: 4 Recent Advances

Did you know that over a million North Carolinians are currently diagnosed with diabetes? That’s 12.4% of our state’s adult population.

I’m one of those affected.

As both a concierge physician and a type 1 diabetic, I make it my mission to stay updated on how to manage both type 1 (less common) and type 2 (very common) diabetes’ many facets.

Type 1 diabetes is a chronic condition that occurs when the body’s immune system destroys the cells in the pancreas that produce insulin. Without insulin, blood sugar can’t enter cells; instead, it builds up in the bloodstream, leading to high blood sugar.

Although type 1 diabetes can begin at any age, it usually starts in childhood. So, with no cure, managing the condition becomes a lifelong challenge. Our blood sugar fluctuates depending on what we eat, how we exercise, and our stress levels or hormonal changes.

To stabilize and maintain a proper blood-sugar balance, we rely on an external supply of insulin, usually injected but also available in an inhaled version. But we must pay careful attention to when and how we dose. Erratic, poorly managed blood sugar levels can create complications:

- Sudden dips can cause loss of consciousness, which is acutely dangerous in the short term.

- Long-range fluctuations can lead to cardiovascular disease, eye disease, kidney disease, and neuropathy.

One Size Does Not Fit All

There’s no such thing as a “typical” type 1 diabetic. Each patient responds uniquely to various foods, physical activity, stress, and insulin doses. Patients can experience frustration and anxiety with their condition and the care regimen it requires.

Insulin is simply a treatment, often not an ideal one. As medical science works to find a cure, science is focused on more physiologic ways to deliver insulin — in other words, automatically provide it in response to blood sugar increases, without the possibility of human error.

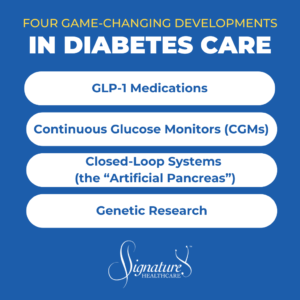

Here are four major developments that have my constant attention:

1. GLP-1 Medications

Glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) agonists are generating a huge buzz. They’re approved for weight loss and for type 2 diabetes. Type 2 is a reduction in insulin sensitivity rather than a lack of insulin production.

GLP-1s are not yet FDA-approved for use by type 1 diabetics. Those who’ve tried the drugs off-label have seen a decrease in hemoglobin A1c (a measure of blood sugar control over the previous three months) of about 0.2%.

However, here’s how GLP-1s may add greater value for type 1 diabetics:

- They’re a catalyst to help overweight type 1 diabetics shed some excess pounds.

- They may decrease insulin requirements, and less insulin means less weight gain.

- They’ve been shown to decrease blood pressure.

- They’ve also been shown to reduce cardiovascular risk in many patients.

One caveat: The GLP-1 class of medications decreases appetite and can cause dips in blood sugars. But for a type 1 diabetic on insulin, that dip could be more pronounced, causing a potentially dangerous side effect: hypoglycemia (low blood sugar).

2. Continuous Glucose Monitors (CGMs)

In the not-too-distant past, type 1 diabetics checked blood sugar levels by finger sticks and before that, urine specimens. None of these procedures made it easy to monitor levels accurately or regularly.

Today, we have better options: continuous glucose monitors (CGMs), which are small sensors inserted painlessly under the patient’s skin that monitor blood glucose for between 10 and 14 days at a time and are much less invasive and burdensome. Both type 1 and type 2 diabetics (and others interested in how their blood sugar behaves) can check their CGM every 5 to 15 minutes for helpful, real-time feedback on their insulin level after they eat or work out, and while they sleep.

CGMs are new ground for type 1 and 2 diabetics. They can see if their blood sugar drops or rises too quickly, then modify their diet, activity, stress level, etc. For example, they may note that having a banana for breakfast causes their blood sugar to elevate. Still, they might find that pairing a banana with peanut butter (some protein and fat) generates less of a spike.

With a CGM device, type 1 diabetics can reduce their A1c by 0.3% to 1%. A 1% drop is much more meaningful to good health than a lesser drop with GLP-1 agonists.

3. Closed-Loop Systems (the “Artificial Pancreas”)

Another game changer for type 1 diabetic patients is a closed-loop treatment system that combines an insulin pump with CGM technology. It’s the closest we have to an “artificial pancreas.”

Closed-loop systems use a CGM that communicates blood sugar levels and trends to an insulin pump or insulin pod, which administers appropriate doses of basal and bolus insulin based on these levels, as well as exercise, sleep, and carbohydrate consumption.

The system can anticipate when a patient’s blood sugar may approach a high level and signals for a small, stabilizing insulin dose. Or, if the CGM notes that a patient’s blood sugar is decreasing, the pump (or pod) algorithm slows or ceases insulin delivery.

Currently, popular closed-loop systems include:

- The Medtronic MiniMed 780G system, the t:slim X2 insulin pump, and the Omnipod (a tubeless insulin pump) all have closed-loop options using various CGM technology, including the Dexcom G7 and the Abbott FreeStyle Libre.

User-friendly closed-loop systems like these help improve the quality of life for diabetic patients. A type 1 diabetic can finally vary the time and content of their diet, rather than eating the same type of food at the same time each day. Many see improved A1cs, better bloodwork, reduced mental burden, and better sleep.

Long-range health outcomes also seem promising, including lower risks of cardiovascular, kidney, and eye disease, retinopathy, and neuropathies over time.

Is a true artificial pancreas a possibility someday?

Pancreatic islet cell transplants have been on the horizon for at least four decades but thus far have not come to widespread fruition.

Also, as with other transplant surgery, the patient requires immunotherapy so the body won’t reject the transplanted organ or cells. Antibodies may attack and destroy the tiny islet cells found in clusters in the pancreas.

However, worldwide, there’s been some limited success with implanted islet cells that block antibodies from attacking the cells. I think we’re getting closer.

Because type 1 diabetics typically contract the disease so early in life, many prefer not to be on a treatment that requires immune suppression. Being on an immune suppressant as a child for the rest of their lives isn’t without potential risks.

There are promising developments in insulin technology, including a “smart” insulin that turns on or off based on blood sugar and its fluctuations.

4. Genetic Research

Genetic research into delaying or preventing type 1 diabetes focuses on identifying specific genes that increase a person’s risk. Here are a few research notes:

- Medical science has known that certain variants in the HLA region of the genome may put people at higher risk of type 1. Now, scientists propose checking siblings or not-yet-diagnosed children of type 1 diabetics for genetic mutations that might place them at risk, too. The idea would be to treat them proactively with disease-modifying immunotherapy or other interventions that may delay or prevent the onset of diabetes.

- People with a genetic risk of diabetes may contract a viral illness that activates that abnormal gene and attacks the pancreas. Some researchers suggest switching off that gene permanently in higher-risk individuals.

- Stem cell therapy may help to make (or replace) beta cells that produce insulin in the pancreas. Because the cells are the patient’s own, the immune system potentially won’t attack them (unless the abnormal gene is activated).

Personalizing How We Approach Your Health

Diabetes research and treatment evolve continually. Perhaps most exciting: There’s a universal drive toward a precision medicine approach. This approach means treatments and therapies tailored to the individual, not to a generalized population.

This trend fits perfectly with the philosophy of concierge medicine that we practice at Signature Healthcare. Regardless of a patient’s state of health:

- Concierge doctors provide personalized attention and a more comprehensive approach in all areas of care. Our goal is to focus on prevention and improve outcomes and long-term quality of life for our patients.

- Because of the nature of diabetes, we offer our patients ready access to our services. We offer longer appointment times and are able to have in-depth discussions with you about blood sugar levels, diagnosis, monitoring, and treatment.

- Suppose there’s an urgent issue, high or low blood sugar, or concern over an illness that might cause blood sugars to fluctuate. In that case, we can address it 24/7 before it becomes more serious.

- Because “it takes a village” to understand the needs of our diabetic patients, we’re happy to interact with a patient’s family as well and offer in-house nutrition and exercise physiology consultations.

- We have the time and interest to explore new technologies, suggest them if appropriate, and create a treatment plan customized for you, collaborating with endocrinologists if needed.

As a type 1 diabetic, I’m excited about all the progress made by current research — and I focus on the positive.

If you’re diabetic (either type 1 or 2), get in touch. We’ll help you make progress, too.

Dr. Jordan Lipton

Dr. Jordan Lipton, a distinguished physician with dual board certification in emergency and ambulatory medicine, co-founded Signature Healthcare and is renowned for his contributions to medical literature and international lectures. Balancing his professional achievements with personal interests, he enjoys squash, skiing, art, and cooking, alongside his wife, Dr. Siu Challons-Lipton, and their two grown children.